Why am I TATT (tired all the time)?

Exhaustion is one of the most complained about symptoms to doctors here in the UK that it even has its own acronym, TATT, which stands for ‘tired all the time’! Despite the world slowing down during the pandemic, TATT still appears to be a common complaint, with many people struggling with exhaustion as lockdown restrictions begin to ease. Here, registered Nutritional Therapist Jen Walpole gives us her insights into why you might be TATT and what to do about it.

Firstly, it’s important to understand what might be driving your symptoms of tiredness or fatigue. Symptoms may be categorised into physical and psychological or a combination of both. We will look at how we can support the physical or medical reasons of fatigue with some of the key nutrients required to support energy as well as addressing some of the lifestyle factors that may be contributing to the psychological symptoms. Finally, we offer some tips on how to boost energy levels naturally.Is anaemia causing your low energy?

Firstly, anaemia is one of the most common reasons for tiredness. Iron deficiency is the most prevalent cause of anaemia worldwide (1). As expected, your blood iron levels are reduced in iron deficiency anaemia so it’s a good idea to get your levels checked out with your GP if you are feeling TATT to check that this isn’t the issue. Nutritionally there is a lot we can do to increase iron levels naturally and very simply, this all centres around increasing your dietary iron intake by consuming both haem (iron from animal sources) and non-haem (iron from vegan sources) iron. The richest sources of haem iron include red meat and liver. However, since it’s advised that we keep red meat to occasional consumption and liver should be avoided if pregnant (due to its high vitamin A content), other good sources include animal products such as poultry, fish and shellfish. Non-haem iron sources include legumes such as beans, lentils, chickpeas, cashews and peas, dark green leafy veg such as spinach and broccoli and seeds such as pumpkin and quinoa. Tofu is a good plant-based source of iron and so is dark chocolate (the darker the better!). Non-haem iron is best paired with foods rich in vitamin C to increase uptake so eat spinach, tomatoes, salads or any other colourful veggies or fruit at the same time. Also, avoid coffee and tea just after meals, as these contain a natural chemical that can bind iron and prevent your body absorbing it efficiently.Is a thyroid issue causing your low energy?

Another reason you might be struggling with fatigue could be the result of an underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism). The thyroid gland’s key role is to control metabolic rate and specifically the rate at which we produce energy. Again, it would be good idea to get your GP to test your thyroid hormone levels which include TSH and T4 or to run a full thyroid panel privately. It’s also a good idea to get your auto-antibodies checked when doing thyroid blood tests. To support the production of the thyroid hormones, we need some key nutrients which include selenium, iodine and the amino acid tyrosine. Both are typically low in the western diet with studies reporting sub optimal selenium levels within UK and Europe populations (2). Brazil nuts are a fantastic source of selenium, with 2-3 per day providing adequate levels. Similarly, in a recent survey, 17% of women aged between 16-49 were found to be deficient in iodine (3). Vegans or those that avoid dairy or fish may struggle to obtain adequate levels of iodine from their diet. Aside from seafood and dairy, seaweeds are a good plant-based source of iodine so including some nori, wakame or dulse flakes in your diet would be a good idea. Whilst tyrosine is a non-essential amino acid, meaning we can produce it in the body naturally, low levels may result in reduction in thyroid hormone levels (4). Fish, meat, poultry, cheese, sesame seeds, soybeans and nuts are all good sources of tyrosine.Are nutrient deficiencies causing your low energy?

Energy production requires some key nutrients and cofactors to support this complex process. For example, the B vitamins such as B2 and B3 as well as iron, sulphur, copper, selenium, and magnesium. The B vitamins can be obtained from meat, fish, dairy, wholegrains and dark green leafy veg such as spinach and nuts including almonds and peanuts. Sulphur can be obtained from allium vegetables, which include garlic, leeks, onions, and shallots. Seafood, shiitake mushrooms, nuts and seeds and dark chocolate are fantastic sources of copper. Finally, magnesium may be obtained from wholegrains and dark green leafy veg (our energy superfood!). Whilst magnesium is the fourth most common mineral in the body (5), involved in over 300 enzyme systems and energy production, it’s worth noting that like a few other minerals, modern soils seems to be more depleted of this. A reduction of magnesium in foods was reported in the UK including a 24% drop in vegetables (6). In addition, one study found that 42% of young adults were deficient in magnesium (7). Finally, B12 deficiency is known to cause extreme fatigue, sluggishness and in some cases, also insomnia (8). Obtained from animal products, B12 must be supplemented by those on a plant-based diet.Another nutrient needed to boost energy levels is CoQ10, which is an antioxidant produced naturally in the body. Low levels of CoQ10 were associated with chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) according to one study, where it was concluded that supplementation might be a good idea (9). However, we can also obtain good levels from organ meats such as liver (not to be eaten in pregnancy), oily fish such as sardines or mackerel, cauliflower, broccoli, lentils, nuts and seeds.

Is stress giving me low energy?

If you want to improve your energy levels, it’s important to address several lifestyle factors such as stress, sleep, alcohol consumption and blood sugar balance. All these factors can add to or may cause fatigue and shouldn’t be overlooked.A little bit of stress can be a good thing, since cortisol (the stress hormone) has various functions in the body including regulating metabolism, inflammation, the stress response, and immune function. The hypothalamus pituitary axis (HPA axis) regulates cortisol levels in the body. However, we need to caveat this with the fact that loss of regulation of cortisol can have a knock-on effect on many systems and may lead to symptoms including feeling TATT. For example, in chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), patients show impaired HPA axis function (10). To support optimal cortisol levels, maintaining a good sleep-wake cycle should be encouraged.

If you are TATT, assess your sleep pattern and incorporate a few simple changes to help reduce your symptoms. For example, getting up in the morning and going to bed at the same time every day is important – even on weekends! Our natural body clock is very much in tune with the daylight so you may find in the summer months you can get up earlier and, in the winter, you may need to get an earlier night. This is fine – embrace it! Use your evenings wisely – often we use this time to complete tasks that we didn’t get to in the day. Instead, try to use your evenings to wind down suitably, ahead of your bedtime. Avoid eating too late and aim to be in bed no later than 10pm ideally. 7-8 hours of good quality sleep per night on a regular basis would be optimal to help reduce tiredness the next day, boost energy levels, and promote optimal health (11).

Is alcohol consumption affecting my energy levels?

It’s well documented that alcohol consumption has a negative impact on overall health and wellbeing. In relation to fatigue, alcohol consumption is associated with insufficient sleep duration and even insomnia. One study hypothesised that it was likely that alcohol is broken down the latter half of the night, resulting in shallow and broken sleep, leading to sleep deprivation over time and symptoms including daytime sleepiness (12). If you are feeling TATT, assess your drinking habits accordingly. Alcohol free days should be encouraged and certainly avoid binge drinking. Keep in mind that the NHS/UK government guidelines in the UK are max 14 units per week for a woman, and many argue that this is too much.Blood sugar and low energy

Finally, in relation to lifestyle factors, balancing blood sugar levels is an important consideration to reduce fatigue and symptoms of TATT. Carbohydrates are the body’s preferred fuel source for energy and should be eaten daily. These include a variety of fruits and vegetables and wholegrains, which turn into glucose to fuel the body. However, not all carbohydrates are created equal. Choosing low Glycaemic Load (GL) foods such as wholegrains rather than simple carbohydrates (for example, white rice) will keep energy levels more stable throughout the day due to reduced spikes in insulin and less of a ‘rollercoaster’ effect on blood sugar levels. This also means avoiding refined sugar found in many processed foods and refined carbohydrates such as shop bought snacks, cakes and biscuits as well as natural foods that contain a high sugar content including dates, fruit syrups and coconut sugar. Studies have shown that consumption of simple carbohydrates has a negative impact on fatigue whilst diets low in these foods showed an improvement in fatigue (13).

It's also really important to pair your wholegrain/complex carbohydrates with protein at each meal as this keeps energy more stable. Nut butter with porridge, and for example cheese/seeds/nuts/legumes/lentils/meat/eggs or fish with lunch and dinner.

Words by Registered Nutritional Therapist, female health specialist and Equi fan Jennifer Walpole

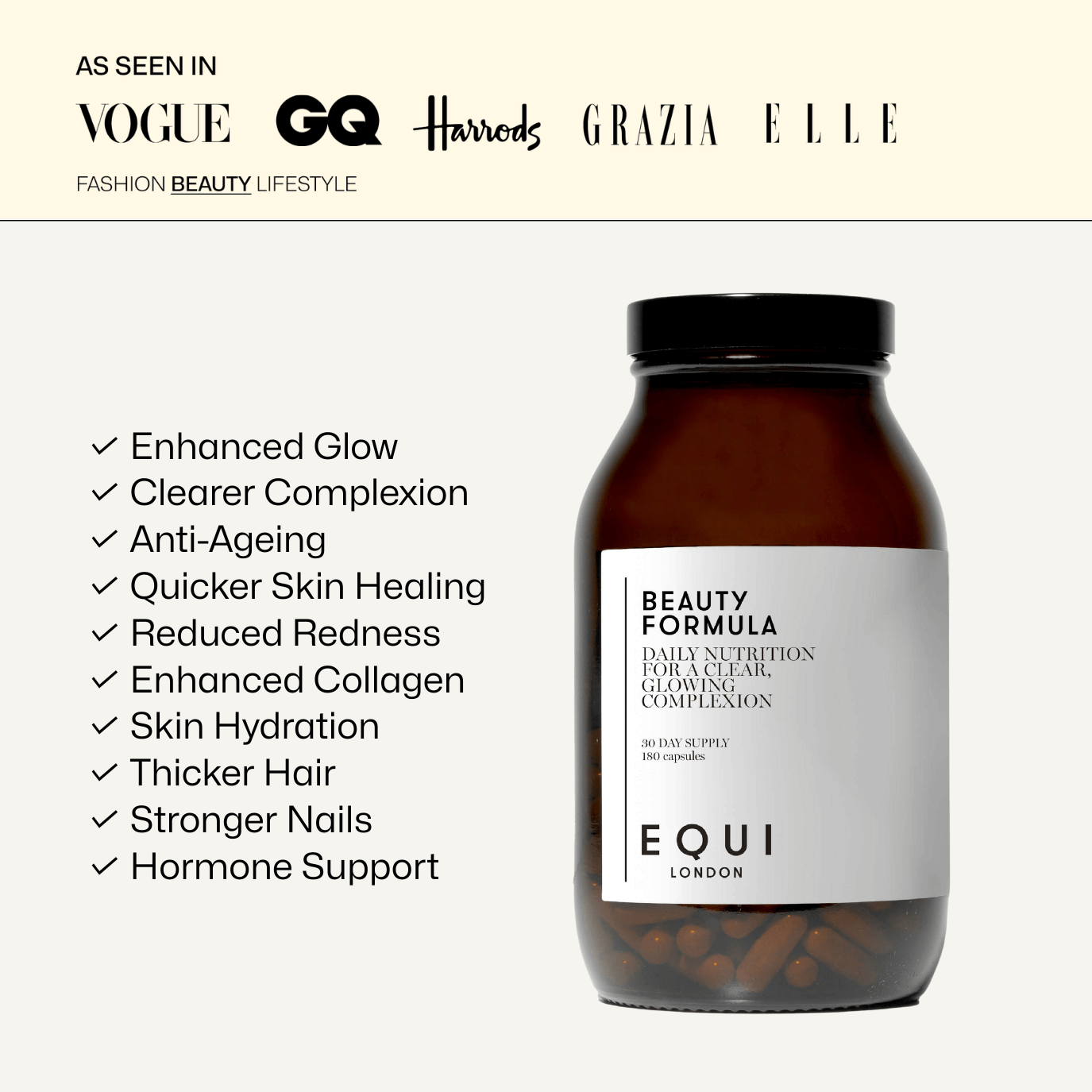

Our Original Formula nutritional supplement for body and mind is a natural way to help boost energy levels from the inside out. Read more about Equi Original Formula here.

References

- Miller, J. (2013). ‘Iron Deficiency Anemia: A Common and Curable Disease’. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine, 3(7), pp. a011866-a011866.

- Stoffaneller, R. and Morse, N. (2015). ‘A Review of Dietary Selenium Intake and Selenium Status in Europe and the Middle East’. Nutrients, 7(3), pp.1494-1537.

- Woodside, J. and Mullan, K. (2020). ‘Iodine status in UK–An accidental public health triumph gone sour’. Clinical Endocrinology, 94(4), pp.692-699.

- Khaliq, W. Andreis, D., Kleyman, A. Gräler, M. and Singer, M. (2015). ‘Reductions in tyrosine levels are associated with thyroid hormone and catecholamine disturbances in sepsis’. Intensive Care Medicine Experimental, 3(S1).

- Schwalfenberg, G. and Genuis, S. (2017). ‘The Importance of Magnesium in Clinical Healthcare’. Scientifica, 2017, pp.1-14.

- Thomas, D. (2007). ‘The Mineral Depletion of Foods Available to US as A Nation (1940–2002) – A Review of the 6th Edition of McCance and Widdowson’. Nutrition and Health, 19(1-2), pp.21-55.

- Sales,H. Nascimento, D.A. Medeiros, A.C.Q. Lima, K.C. Pedrosa, L.F.C. Colli, C. (2014). ‘There is chronic latent magnesium deficiency in apparently healthy university students’. Nutricion Hospitalaria, 30 (1), pp. 200-204.

- Hunt, A. Harrington, D. and Robinson, S. (2014). ‘Vitamin B12 deficiency’. BMJ, 349(sep04 1), pp. 5226-5226.

- Maes, M. Mihaylova, I. Kubera, M. Uytterhoeven, M. Vrydags, N. Bosmans, E. ‘Coenzyme Q10 deficiency in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic faigue syndrome (ME/CFS) is related to fatigue,autonomic and neurocognitive symtpoms and is another risk factor explaining the early mortality in ME/CFS due to cardiovascular disorder’. Neuro Endocrinology Letters. 30 (4), pp. 470-6.

- Roberts, A., Wessely, S., Chalder, T., Papadopoulos, A. and Cleare, A., 2004. Salivary cortisol response to awakening in chronic fatigue syndrome. British Journal of Psychiatry, 184(2), pp.136-141.

- Watson, N., Badr, M., Belenky, G., Bliwise, D., Buxton, O., Buysse, D., Dinges, D., Gangwisch, J., Grandner, M., Kushida, C., Malhotra, R., Martin, J., Patel, S., Quan, S. and Tasali, E., 2015. Recommended Amount of Sleep for a Healthy Adult: A Joint Consensus Statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society. SLEEP.

- Chakravorty, S., Jackson, N., Chaudhary, N., Kozak, P., Perlis, M., Shue, H. and Grandner, M., (2014). Daytime Sleepiness: Associations with Alcohol Use and Sleep Duration in Americans. Sleep Disorders, 2014, pp.1-7.

- Pharr, Jennifer R. (2010) "Carbohydrate Consumption and Fatigue: A Review," Nevada Journal of Public Health: Vol. 7 : Iss. 1 , Article 6.

Disclaimer: Certain supplements are used for different reasons and a one-size-fits-all approach shouldn’t be adopted. In addition, pregnant women and anyone on medication should always consult a doctor before embarking on a supplements programme. As with all articles on www.equilondon.com, this is no substitution for individual medical or nutritional advice.